Earlier|Later|Main Page

About all manner of pharmaceutical scientific misconduct, bad science, and related curious incidents. If you're not outraged, you're not paying attention.

See Wall Street Journal, 11 May 2007 Scientists Draw Link Between Morality And Brain's Wiring.Hat tip S.S for neurology.

"To analyze their moral abilities, Dr. Koenigs and his colleagues used a diagnostic probe as old as Socrates -- leading questions: To save yourself and others, would you throw someone out of a lifeboat? Would you push someone off a bridge, smother a crying baby, or kill a hostage?

The effort to understand the biology of morality is far from academic, said Georgetown University law professor John Mikhail. The search for an ethical balance of harm is central to medical debates on vaccine safety, organ transplants and clinical drug trials."

Feeling mistreated can hurt, especially when it comes to the heart (1).

Feeling mistreated can hurt, especially when it comes to the heart (1).

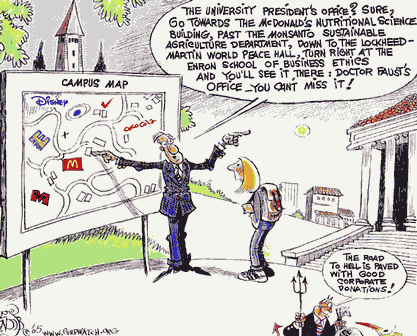

I laughed out loud when I read the today's Guardian article about the "new" UK research integrity panel (UK-PRI).

I laughed out loud when I read the today's Guardian article about the "new" UK research integrity panel (UK-PRI)."I said to them, '70,000 people have been butchered and none of you gave a shit.'"

There was silence. A priest had sworn in the pulpit.

"And the reason I know none of you gave a shit," he continued, "was because none of you fell off your seat when I said '70,000 had been butchered', but nearly all of you fell off your seats when I said 'shit'."

For the background to this sermon and its consequences read here. Much of Gilhooley's feelings about the church would apply to the current sad state of medicine.

For the background to this sermon and its consequences read here. Much of Gilhooley's feelings about the church would apply to the current sad state of medicine. My attention has just been drawn to this ongoing important court hearing in the UK discussed in the Observer article below. Apparently yet another case of an institution not being totally open when dealing with potential offenses against patients. We have the usual secret investigations, as well as poor treatment of whistleblowers and those who come to the defense of whistleblowers.

My attention has just been drawn to this ongoing important court hearing in the UK discussed in the Observer article below. Apparently yet another case of an institution not being totally open when dealing with potential offenses against patients. We have the usual secret investigations, as well as poor treatment of whistleblowers and those who come to the defense of whistleblowers.Medical school accused of cover-up after claim that surgeon retained samples without consent

Antony Barnett Sunday February 25, 2007 The Observer [Link]

Allegations that patients at a Liverpool hospital had parts of their brains removed for medical research during neurosurgery without consenting to the procedure, can be revealed today.

The University of Liverpool is accused of covering up the procedures, alleged to have resulted in at least 12 patients having brain parts removed. Its medical school, which was embroiled in the Alder Hey organ retention scandal, is facing claims that it tried to silence a senior hospital whistleblower who raised the alarm about alleged misconduct by a leading brain surgeon.

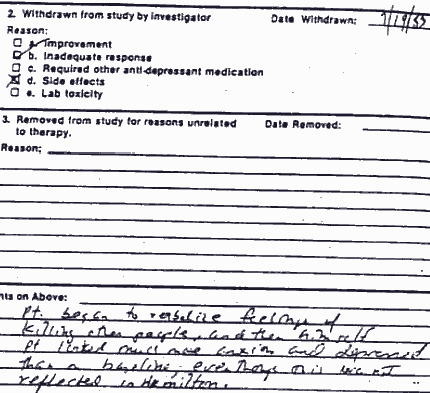

Until 2005, the university employed Professor Peter Warnke, who was chair of neurosurgery and operated at the Walton Centre hospital. In 2002, allegations surfaced that Warnke had been taking tissue from the brains of living and dead patients at the Walton Centre without obtaining consent.

Warnke is alleged to have taken samples of brain tissue during surgery, freezing them in liquid nitrogen, marking them with a black dot and sending them to Genpat 77, a private biotechnology company in Germany. The samples were used to test a new treatment for brain diseases involving an antibody called TIRC 7. Warnke was a joint owner of the patent taken out on TIRC 7, along with the founder of Genpat 77. Warnke has always vigorously contested claims of wrongdoing. The Observer has established that, at around the same period, Warnke attempted to obtain tonsils that had been removed from patients at the Aintree Hospital in Liverpool for use in associated research. Elizabeth Preston, the hospital's medical director, said: 'I can confirm that Professor Warnke did ask for tonsils, but a nurse questioned whether he had ethical consent. He was refused and as far as I am aware he never had access to any tissues from Aintree.'

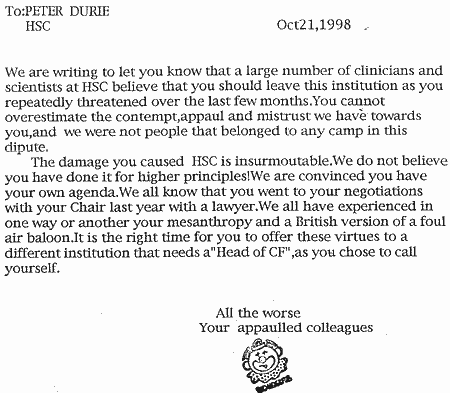

Both the nurse and a surgical colleague of Warnke's raised questions about his conduct with Dr Marco Rossi, who then chaired the regional ethics committee set up to improve research standards after the Alder Hey scandal, where hundreds of children's organs were retained without parents' consent. Rossi, who was a consultant neuropathologist at the Walton Centre, claims that when he began investigating the allegations against Warnke he suffered threats from senior staff at the university's medical school. He claims that the level of intimidation made him ill and he was unable to continue his work.

Rossi is suing the Walton Centre, the University of Liverpool and the strategic regional health authority for breach of contract. He argues that as a senior employee and whistleblower they should have protected him, and claims that senior medical school staff were more concerned in covering up a potential scandal. He alleges that he was subjected to a campaign of bullying and harassment in an attempt to get him to withdraw his accusations. In court, the university has argued that Rossi's allegations about Warnke were irrelevant and should not be heard.

Last week, a judge rejected this and ordered the university to

hand over its dossier on the affair, including an internal investigation into Warnke's conduct. The court has heard that Rossi alleges that dozens of ethical consent forms used by Warnke for his research were either incomplete or inaccurate.

Although Rossi left in 2002, no action was taken against Warnke until April 2005, hours after Rossi launched his legal action. Warnke was suspended and later resigned. In November 2006 he was appointed chief of neurosurgery at the Beth Israel hospital in Boston, part of Harvard Medical School. Warnke had previously served on the Post-Redfern Committee, which was set up at the University of Liverpool to investigate the Alder Hey scandal.

The university had employed the Dutch pathologist, Professor Dick Van Velzen, who was found guilty of serious professional misconduct for retaining children's organs from 1988 to 1994.

The British law firm Weightmans, which is acting for Warnke, issued a statement to The Observer rejecting Rossi's claims. It said the allegations against Warnke were 'brought by a disgruntled former employee and a colleague of our client'. It added that the allegations were the subject of an independent investigation by the General Medical Council in 2005, which, in January 2006 wrote to Warnke stating they would take no further action [comment: now that's a surprise].

A spokeswoman for Liverpool University said: 'In the context of the current proceedings it would be inappropriate for the university to comment.'

Mel Pickup, chief executive of the Walton Centre, said: 'We would like to reassure former patients of the Walton Centre that at no time have there been any concerns about patient safety or appropriate patient care provided by the individuals connected with this case.'