This rating was determined based on the presence of the following words:

drugs (12x) suicide (5x) pain (4x) death (1x)

I'm off to Montreal and Toronto for the next week to present some science.

Earlier|Later|Main Page.

About all manner of pharmaceutical scientific misconduct, bad science, and related curious incidents. If you're not outraged, you're not paying attention.

Matthew Holford has been discussing the rather interesting case of Professor Martin Keller at Brown University. See

Matthew Holford has been discussing the rather interesting case of Professor Martin Keller at Brown University. See Article 1: Bass A. Brown researcher faced billing questions in past.But then a few months later the following appeared

Boston Globe, January 21, 1996. P.21.

The article notes: In 1994, Keller was investigated by the Rhode Island Attorney General and the Police for "padding his travel expenses." The financial crimes unit of the Police said that the case was dropped after the University requested that it be handled internally. The University spokesman (Mark Nickel) denied that "the university interceded to halt the investigation. Keller first denied the allegations, saying there was "absolutely no truth" to them. Later he acknowledged the audit, but said it found that Brown owed him money. In fact the audit found overbilling that "amounted to several thousand dollars." Keller eventually repaid the University $918.

Article 2: Bass A. Ex-employees allege harassment by Brown.One year later Professor David Kern's research was destroyed by Brown University when he attempted to tell the truth about a disease.

Boston Globe, June 24, 1996. P. 17.

The article notes: Multiple Brown employees who expressed concern about Keller's travel finances and other problems in the Psychiatry Department said they had been abused by Keller and other Brown administrators as a result. Diane Hanks, a former technical writer at Brown alerted Brown officials to problems in Keller's travel budget. Hanks wrote to Brown University President Vartan Gregorian, "It has been evident to me since March 1993 that I would never be allowed to advance my career within the university. How odd that the university chose to punish me, and so many others, rather than to deal with Dr. Keller." Former executive secretary, Patty Kostka, said that staff members who were funded by federal research grants "were actually doing research for drug companies, such as Upjohn." and "It really shocked me to see federal grant money used for drug companies. But when I questioned it, they took away my duties and assigned them to someone else." Donna Howard, a former assistant administrator said "the deans were all aware of what was going on in Keller's department, and they were certainly aware of problems with the Corrigan contract. But they chose not to do anything about it. I guess they considered myself, Diane, and other employees more expendable than Marty Keller."

Unfavourable Bias? by Giles 31/5/2007

I have an unfavourable bias towards a lot of things. Crime (especially violent crime), war, New Labour corruption, racism, English tabloid newspapers, child abuse, chavs, drunks and junkies (these three are often the same thing), corporate exploitation of the poor, environmental destruction for financial greed, Jehovah’s Witnesses, trial without jury, prescribing antidepressants to children; the list of my “unfavourable biases” is quite long really. Anything that makes innocent people miserable tends to make me unfavourably biased toward it.

Yet I’m also of the opinion that the pharmaceutical industry as a whole has done far more to improve the life of Joe Public than it has to harm it. For every Vioxx or Seroxat, there are at least fifty different drugs that make a huge and positive difference to millions of people’s lives, day in, day out. For over twenty years, I was proud to work for pharma and was equally proud of my own modest contribution to the overall well-being of mankind, which to me should be the industry’s main consideration. It’s the relatively recent phenomenon of “Big Pharma” that bothers me. These vast corporate behemoths have pretty much superseded the multiplicity and diversity of small individual companies, bringing in the “buckets of money” mentality that has largely driven out the “patient need above all else” philosophy of 20 years ago.

Yet despite all that, I still love the pharmaceutical industry, although you might not guess that from the nature of this blog. I just don’t like those in charge of it or their behaviour.

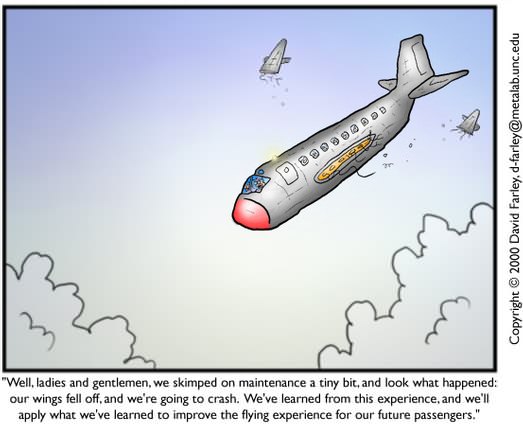

So I don’t think that I have an “unfavourable bias towards the industry” at all. I love it. It’s just that there’s a difference between the way that I love the industry and the way some of its cheerleaders do. I love the pharmaceutical industry in a grown-up way. I want it to do well and I want it to do good. I despair when its leaders run it off the rails and into the mud, in much the same way as a parent despairs when a much-loved son or daughter starts “hanging out with the wrong crowd”. In my own tiny and insignificant way, I try and point out the error of its ways by showing how corrupt and greedy its actions can be or are perceived to be. It’s my hope that a groundswell of similar collective opinion will lead to either a change of heart within pharma’s senior leadership, or to penalties for malfeasance that cannot be sustained by them. Either will do for me.

Pharma cheerleaders and their “Astroturf” blogs (the artificial ones with corporate backing, rather than genuine “grass-roots”) seem to love the industry in a different way. They appear to love it in the same completely uncritical way that a four year old loves their Mommy. Mommy provides security and comfort. Everything Mommy does is therefore wonderful and anyone who criticises Mommy must therefore be bad. Or, as they prefer to say, a disgruntled loser.

I’m a nobody when compared to better-known pharmawatchers such as Dr. Rost and Jack Friday. I can’t really speak for their motivation, but I’m sure none of us criticise the pharmaceutical industry out of hatred for it. We criticise it because we want it to get better. We want it to stop killing people by pushing through improperly tested drugs with dubious safety profiles, or burying adverse trial data, just for quick profits (Vioxx, and now Avandia?). We want it stop practices such as off-label sales, which (for example) led to thousands becoming addicted to Purdue’s OxyContin. We want it to stop buying politicians and start listening to its customers when it comes to drug pricing issues. Maybe, just maybe, the pharmaceutical industry can then start to win back the public admiration it had twenty years ago.

The cheerleaders hide behind current the status quo, saying things like “there’s no such thing as a risk-free medicine” when it is obvious that risks are being wilfully glossed over and regulations ignored with impunity. They dismiss industry critics or whistleblowers as being losers with a personal agenda rather than people with enough knowledge to know that corners are being cut and people's well-being endangered as a result, all solely in pursuit of profits.

The pharmaceutical industry is facing a massive innovation gap and a growing resistance to its current operating practices. It won’t meet those challenges by pretending everything is great, hammering its critics or buying short-term political support.

Professor Nelson Watts chairs the FDA Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee. Of current interest, this is the committee that recommended the 1999 approval of GSK's Avandia (rosiglitazone). He is also Professor and Director at the University of Cincinnati Osteoporosis Center, home of Procter and Gamble.

Professor Nelson Watts chairs the FDA Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee. Of current interest, this is the committee that recommended the 1999 approval of GSK's Avandia (rosiglitazone). He is also Professor and Director at the University of Cincinnati Osteoporosis Center, home of Procter and Gamble. Reply Nelson Watts to Barbara Quart - 24 April 2007:

Reply Nelson Watts to Barbara Quart - 24 April 2007:

Attendre que de soi la vétusté triomphe,Monogomphe; a brilliant Hellenism signifying "who has but a single tooth".

C'est absurde! Je vais au devant de la mort.

Mourir a plus d'attraits quand on est jeune encore:

A quoi bon devenir un vieillard monogomphe?

"There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root"

"There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root"Big Pharma is big dog at symposiumEarlier|Later|Main Page

By Barbara Quart (Original Article)

May 28 2007 NEW YORK LATE LAST month I attended the 7th International Osteoporosis Symposium in Washington, D.C. I thought I'd learn a lot that I could then pass on to other older women in the Berkshires, many as little conscious of osteoporosis as I had been, and I hoped to get clearer what to do about my own diagnosis, and the urgently prescribed medication for it, which I have refused for a year now.

The event was basically a five-day non-stop education — some might call it a fancy sales job, or even indoctrination — by MDs for MDs (also physical therapists and other health professionals). From 8 a.m. to 9 p.m., talks and panels, lots of exciting information, in grand hotel ballrooms. All meals provided — dinners especially nice, supplied by the drug companies — plus nifty perks like a handsome tote bag emblazoned with "Lilly" (maker of Forteo, scariest of the drugs), and a beautiful pen inscribed "Fosamax," the blockbuster seller. A very different world from the pretzels and chips and cheap white wine of my own decades of university English literature meetings. I feel grateful now, thinking back, that one couldn't be for sale in my profession.

After I came home I thought for a while that things seemed clearer. Just about everyone who spoke or whom I spoke to seemed of one mind: this is a really bad disease, undertreated, it desperately needs to be publicized, diagnosed (give a DEXA scan to every woman over 65), and medicated, or it will wreak devastation. And I heard about several memorable instances of osteoporosis-caused spinal collapse, hip collapse, chronic horrible pain, hideous operations.

So my first draft of this article read like the NIH ad in the recent Sunday Times Magazine devoted to older women. I crammed it full of data, carefully defining the disease (bone thinning, especially after menopause), listed risk factors (like family history and smoking), noted how men get it too but later and to a lesser degree, urged kale and yogurt, heavy vitamin D3, exercise overseen by a really skilled physical therapist (working with amazing Jill Esterson of Great Barrington was the best thing I did this last year).

I couldn't however share the leadership MDs' enthusiasm for the drugs as good, safe, effective; nor their repeated deploring of "non-compliance" (naughty patients who drop their meds). The scolding of the "non-compliant" seemed to have priority at the symposium over the exciting talks by research scientists, and no speaker dealt with why so many people go off these drugs or are reluctant, like me, to take them in the first place.

There was a giant image of jaw necrosis: the white patch of exposed bone in the mouth from taking a bisphosphonate (Fosamax or Actonel) — though no mention of the horrific pain, or how some cases heal but others don't, and for those there is no help. And little or no mention of esophageal problems, from heartburn to severe terrifying esophagitis. Nor leg pain, eye pain, other "adverse events."

The tone was always upbeat, a kind of beating the drum, and the line between the drug companies and the MDs uncomfortably unclear. True, the dinner panels are called "industry sponsored satellite sessions" — but the same leadership MDs who are major speakers during the day, and whose names keep appearing on the important research in the major medical journals, are the same ones on the evening "satellite" sessions that subtly but unmistakably sell the drug — Forteo, Actonel, Fosamax — sponsoring the session.

Health professionals I respect argue that osteoporosis is being hyped to create a massive new market to take over where the disastrous Hormone Replacement Therapy left off, all the money it generated vanishing. True or not, money weaves through all of this in disconcerting ways.

Before I left for Washington, I stumbled upon an on-line story in Slate about two Sheffield University (England) researchers conducting clinical trials of Actonel (second in sales to Fosamax) for Proctor & Gamble for $250,000. But P&G took away the final data, denied them access, wanted to ghostwrite the conclusions for publication under their signatures.

One of the scientists, Aubrey Blumsohn, refused and insisted on seeing the data first, only to find that 40 percent had been removed. This a year after medical journal editors "warned that growing industry interference with academic research (from study design to data analysis and publication) was threatening the objectivity and trustworthiness of medical research."

As former New England Journal of Medicine Editor Marcia Angell, MD of Harvard Medical School and author of a book on the subject, states that drug companies are "involved intimately in every detail of the research" for new drugs, and "they design the research so that their drugs look better than they really are." How could one ever again trust any scientific study, in however reputable a journal? What won't I know about?

So in my own looking for some truth I could rest my decision on, I discovered that even the truths I thought I already had are probably not trustworthy. Compromised doctors. Compromised data. Flying blind indeed.

So perhaps it's not surprising that what stays with me most from the symposium is the only critical voice I heard in five days, a gray-bearded man who spoke with quiet grace after the final session. An orthopedic surgeon from a small town near Pittsburgh, he said he feared we are walking into yet another medical disaster of huge proportions and the people treated will be the ones who will pay the price. He himself prescribes these drugs because he feels something must be done to intervene with continual bone loss in his elderly patients. But it will be another 15 years before we know what we're doing. When you take this medication, he said to me later, you should see yourself as being in yet another clinical trial.

Finally, I contacted the medical consumer advocate whose sanity in print I've long valued. BMD numbers are critical, she says, and you must assess what exactly the drug will do for you. How effectively does it prevent fractures? Percentages can be made to look large but may actually be very small, barely more than the placebo effect, perhaps the same as the chance of an esophageal ulcer. Is that worth the risk? The whole industry is trying to terrify you, she says.

My own conclusions? I feel I must take that pill, but I will do so angrily.

I am angry that this richest of American industries uses its vast wealth far less for research to make better, less dangerous drugs, than to buy off doctors; to plaster misleading ads everywhere; to dispatch armies of salesmen and lobbyists; and to manipulate and thus destroy the meaning of scientific research results. Still, as I write this, stories and editorials are suddenly erupting in the Times about MD/drug company collusion; and Vermont's Bernie Sanders eloquently attacked Big Pharma in the Senate itself as the very worst of a long list of the most powerful, greediest special interests in America.

So maybe there's hope.

But for now, dear reader, sorry, but you're entirely on your own.