- The amount of money involved is large. In 2003 drug companies spent US$448 million on advertising in medical journals [1]. The American Medical Association (AMA) receives at least US$40 million annually from advertising[2].

- It is effective at increasing sales. Analysts calculate that the return on investment is about $5.00 for each $1.00 advertising spend [3].

- Advertising in general medical journals is almost exclusively for pharmaceuticals, and not other medical products, or consumer products of interest to doctors (computers, holidays and so on). Many journals have statements which exclude general consumer advertising [1]. For example the JAMA states "products or services eligible for advertising shall be germane to, effective in, and useful in the practice of medicine". It is proposed that accepting advertising for consumer goods would help minimize the conflict of interest inherent in pharmaceutical advertising, and would free editors from threats[1] made by advertisers which leads them to participate in editorial scientific fraud. Another option is to eschew journal advertising altogether (as has PLoS Medicine).

- "Military recruitment advertisements" were noted in JAMA as an important exception to pharmaceutical advertising[1]. During a single anomalous year (1997) JAMA ran advertisements for Land Rover vehicles, Steinway pianos, Wellcraft boats, pork, and Quaker oatmeal [1].

- The exclusivity of pharmaceutical advertisements is not due to affordability. After adjusting for circulation rates, advertising rates in medical journals are far less expensive than rates in consumer magazines (such as Vogue) [1].

- Various inappropriate "mottos" of journals are discussed [1]. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and metabolism states: "we use our know-how to help you reach the industry's thought leaders and maximize your return". The NEJM states "Place your ad in the New England Journal of Medicine and make our relationship with the medical community yours". The BMJ states "We protect our reputation by careful balance of editorial and advertising, which means your messages will always stand out".

- Advertisements are not "educational". The American College of Physicians (publisher of Annals) colluded with this excuse by arguing in court that profits on pharmaceutical advertising should not be taxed because advertisements were educational. Justice Marshall judged "we are bound to conclude that the advertising in Annals does not contribute importantly to the Journal's educational purposes"[4]. The notion of advertisements as "educational" is easily rebutted. Although there are more than 10,000 drugs on the market, 50% of the advertising expenditure is on only 50 of these. Competing drugs regularly cohabit in the same journal. Reviews of pharmaceutical advertisements conclude that 44% would lead to improper prescribing [5], about 60% of cited research was company sponsored, and 30% of advertisements with medical claims contain no scientific references. 19% cited "data on file" that is not open to scrutiny [6], impossible to obtain [7][8] and therefore potentially false.

- Apart from influencing doctors, advertising (or the threat of its withdrawal) is used to manipulate editorial decisions [1]. Several examples are given. In 1992, a study in Annals criticized the accuracy of advertisements in journals [5]. Large pharmaceutical companies subsequently withdrew advertising in that journal [7]. In 2004, an editor at Dialysis and Transplantation told an author that although the author's article had passed both editorial and peer review, the marketing department rejected it. The journal later reversed its decision, but the author refused to resubmit." [1].

- Fugh-Berman, Adriane; Karen Alladin, Jarva Chow (2006-06-01). "Advertising in Medical Journals: Should Current Practices Change?". PLoS Medicine 3 (6): e130. Retrieved on 2008-03-16.

- American Medical Association [AMA - 2004 Annual report]. AMA (2005). Retrieved on 2008-03-16.

- Neslin, Scott (2008-03-16). ROI Analysis of Pharmaceutical Promotion (RAPP) - An Independent Study. Retrieved on 2008-03-16.

- American College of Physicians v. US. 3 Cl.Ct 531 (1983)

- Wilkes, M S; B H Doblin, M F Shapiro (1992-06-01). "Pharmaceutical advertisements in leading medical journals: experts' assessments". Annals of internal medicine 116 (11): 912-9. PMID 1580449.

- Cooper, Richelle J; David L Schriger (2005-02-15). "The availability of references and the sponsorship of original research cited in pharmaceutical advertisements". CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal=journal de l'Association medicale canadienne 172 (4): 487-91. PMID 15710940.

- Mindell, J; T Kemp (1997-12-13). "Evidence based advertising? Only two fifths of advertisements cited published, peer reviewed references". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 315 (7122): 1622. PMID 9437300.

- Hafeez, A; Z Mirza (1999-08-28). "Responses from pharmaceutical companies to doctors' requests for more drug information in Pakistan: postal survey". BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 319 (7209): 547. PMID 10463894.

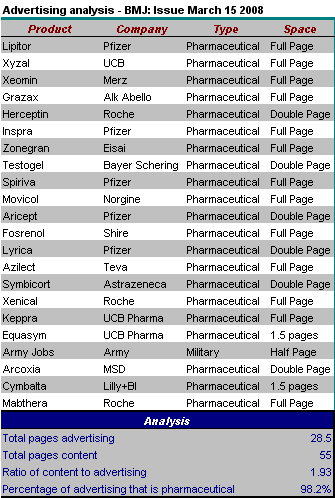

This is the British Medical Journal Advertising analysis for this week.

New records have been set for the amount of advertising, and the ratio of advertising to content. The single half page that was not devoted to pharmaceutical advertising was for the army. Unfortunately both the problematical (evidence free) advertisement for testosterone, as well as the Pfizer fireman (? a fake fireman) were back.

Rules: As usual this is for the UK version of the BMJ. The classified advertisement section is excluded, as are advertisements for the BMA, products of the BMJ/BMA/BNF or the government.

Click here for collated BMJ Advertising analyses.

Earlier|Later|Main Page

No comments:

Post a Comment